Educators respect and value the history of First Nations, Inuit and Metis in Canada and the impact of the past on present and the future. Educators contribute towards truth, reconciliation and healing. Educators foster a deeper understanding of ways of knowing and being, histories, and cultures of First Nations, Inuit and Metis.

Standard 9 may be simultaneously the most challenging and most important of all the educator standards. In Canada especially, we as educators have a duty to our students and our broader communities to do our part in understanding our own prejudices and biases and helping to heal the deep-inflicted and long-lasting wounds of our colonial past and present. This is something that I especially found difficult to work on as someone firmly rooted in science education. I care deeply about history and the righting of the many injustices that exist within it, but I wasn’t sure how I could go about addressing these sorts of topics in a science classroom in a way that didn’t feel forced or inappropriate.

The introduction of FPPL to our classes in the UNBC education program was a turning point for my understanding of standard 9. I came to the realisation that much like the new BC curriculum, I should be focused on big ideas and competencies rather than content. This of course doesn’t mean that there doesn’t need to be Indigenous content, but more so that delivery and cultural understanding was the most important thing. Throughout my experiential practicum, I tried to navigate lessons through the principles of learning, ensuring that the goals of the lesson lined up with the goals of the principles. I still struggled with not having the level of Indigenous content in my lessons as I would have liked, and I was frustrated because I felt like the content of the curriculum was holding me back. It was at this point that I spent some more time looking through the FNESC First Peoples Science 5-9 text and it gave me an idea.

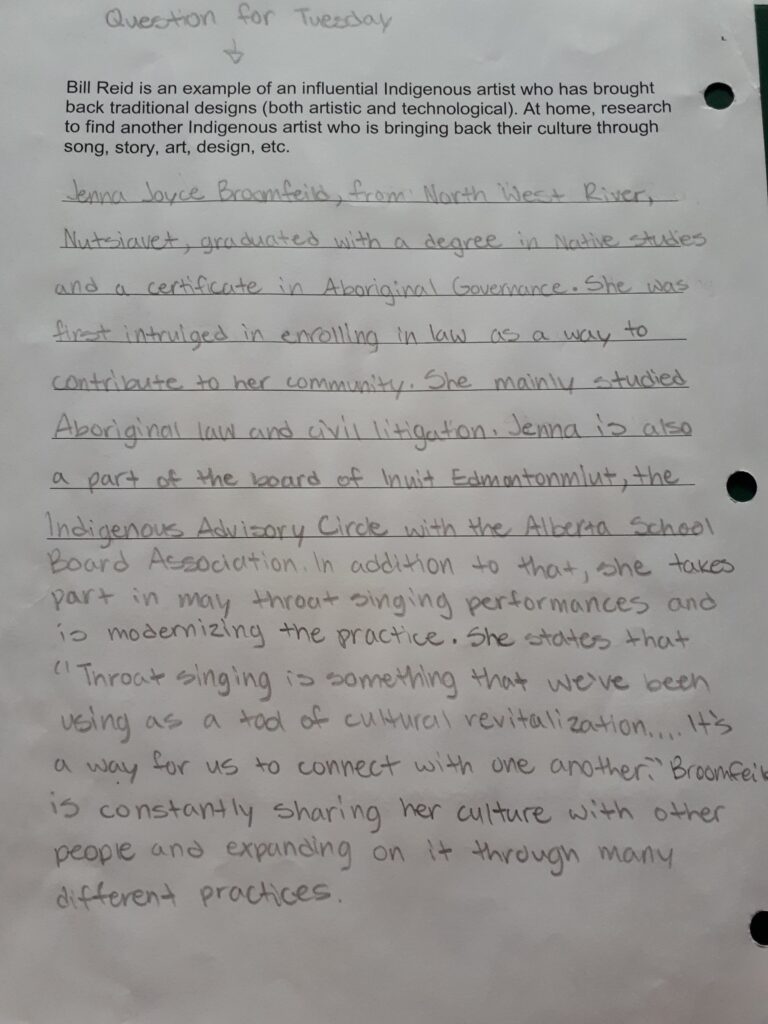

In my class at the time, we were looking at the properties of matter. This is a pretty broad subject and so far we’d spent quite a bit of time identifying properties of common things we see around the house: foods, appliances, jewelry, furniture, etc. The thought occurred to me, “these are all things they mostly already know, we should probably get into WHY it might be important to be able to identify these properties”. That is when I looked through the FNESC resource for anything on properties and found a nugget of gold on page 74 that talked about properties of different types of wood. I combined this resource with some information from the SFU Bill Reid Centre to make an activity. In this activity, students were asked to consider what properties the tree that was used to make dugout canoes (Western Red Cedar) likely has, and why that would be beneficial for its function. This was coupled with information on the traditional aspects of canoe-making, and some insight into how these traditions were lost through government oppression. To go along with the more science-based predictions of properties, I also asked the students to do some research on their own on an Indigenous artist of their choosing who is bringing back their culture through art, story, song, design, etc. This more open-ended small research assignment went well, with a wide variety of responses, some even choosing relatives to talk about. I’ve included an exemplar below from one student who really bought in on the assignment.